Are We Serious About Our

IT-Services Industry?

There are a couple of noteworthy but underrepresented elements in the mainstream discourse about Nepal’s IT services industry. First, this industry has grown not because of but rather, in-spite of the Government of Nepal (GON). Second, despite the social media hype, this industry is still in its infancy and nowhere near the mechanically cited “half a billion dollar industry”. And third, realizing exponential growth in export-oriented IT services is the most immediate and achievable option to accelerate sustainable, equitable, and inclusive job growth over the short-to-medium term.

In one example after another, where IT services have graduated into the mainstream, there is evidence of constructive, forward-looking public sector support to create enabling environments along with sizable public sector investments. The Silicon Valley that we know grew off the back of funding and research enabled by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) starting in the 1950s; the IT sector in the Singaporean city-state grew out of a recognition of geographical limitations to traditional growth paths when that country was founded in the 1960s; India’s policy reforms that targeted the IT sector in the 1980s and nineties eventually gave rise to the juggernaut that is India’s IT services industry today.

In Nepal’s case, the experience has been almost entirely entrepreneur-driven. Nepal’s tech industry has innovated business models while regulators and policy-makers have struggled to keep pace. This is why Nepal’s digital ecosystem is replete with examples of reactive posturing by GON on everything from retroactive VAT dues to taxation of capital gains on ownership transfers in off-shore jurisdictions.

A cynical view of such misguided attempts paints a bureaucracy that is intent on punishing success and stunting the growth of Nepal’s IT services industry. A more balanced take suggests a bureaucracy that is implementing anachronistic rules atop an industry with multi-jurisdictional business models that they simply do not understand. Add to this confused state the introduction of assumption-laden data points and compound this confusion by endlessly regurgitating a sensational narrative on the potential of Nepal’s IT services sector, and the gap between reality and a make-believe world worth hundreds of millions of US dollars (if not billions), sets in.

From a valuation perspective, and because Nepal’s export-oriented comparative advantage is services (not products), trading multiples for Nepal-based counterparts of foreign domiciled companies are naturally subdued. From a revenue standpoint, the business model that Nepali companies have successfully deployed is as cost centers for their foreign-domiciled (parent) entities. This lays bare an obvious but glossed-over contradiction in forecasts about the potential of IT services in Nepal – i.e., the assumed availability of a skilled and growing IT labor pool into the indefinite future.

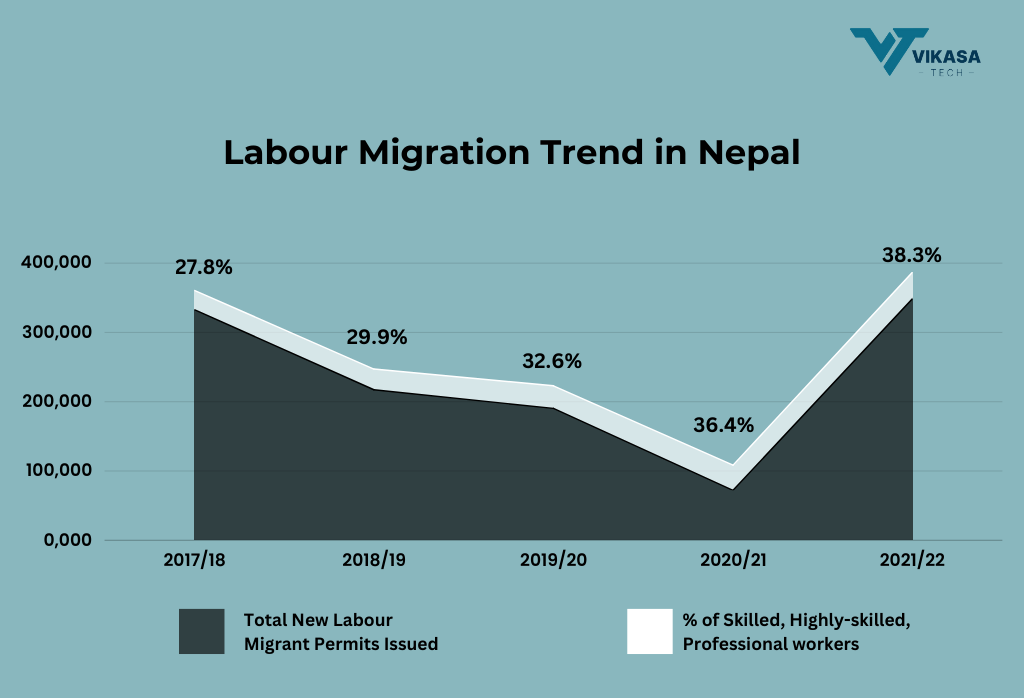

The labor conditions required to evolve from the current state to a future where Nepal is a destination for IT services is not assured. To the contrary, migration data suggests the opposite trend: Nepali youth, the backbone of a desired services sector boom, are leaving Nepal is search of gainful employment in staggering numbers. Part of this exodus is almost certainly the youngest and most qualified IT professionals that the Nepali ecosystem has to offer.

This hypothesis is tested and proven by considering that most of the highly celebrated outsourcing companies in Nepal are busy setting up operations in tier-2 and tier-3 cities in India and elsewhere. This dynamic is on the rise because over time, wage rates naturally gravitate toward market-clearing levels regardless of physical location. In this eventuality, the rational approach for corporate decision-makers will be to grow their businesses in jurisdictions where the supply of IT labor is relatively abundant, and the regulatory environments are predictable. Without deliberate action, Nepal is not well-positioned on either of these fronts.

These considerations lead to a simplistic outlook: for export-oriented IT services in Nepal to reach its potential, one must consider not just the theoretical potential of global demand but also the practical limits of a faltering labor supply-base in this country. In addition, one must also account for upward pressures on prevailing IT services wage rates in Nepal, which seek equalization with global benchmarks adjusted for factors like the relative cost of living. This dynamic entails margin compression for Nepali IT services businesses on the one hand and consequences for IT products and services for the domestic market, on the other.

There is a substantial and unmet role for GON in helping enable the transition from academic forecasts to a reality of exponential growth in IT services. While attempts over the past five years to convert the Digital Nepal Framework (2019) into investments in public digital infrastructure and policy reforms have been less successful, efforts underway including those under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister through Nepal’s eGovernance Commission offers hope at a streamlined policy environment with positive knock-on impacts for Nepal’s IT outsourcing industry.

Further, there is room to do a lot more in areas such as digital (re)skilling to meet the anticipated labor demand for Nepal’s “billion dollar” IT services industry. This is a complex endeavor but if thoughtfully implemented, entails benefits for the entire digital ecosystem. GON participation in a PPP model, similar to that of India’s National Skill Development Corporation, could be an avenue to be explored.

Nepal has a small but fast-shrinking window of opportunity to reposition its economy as a global outsourcing powerhouse. Success on this front would be far more transformational and impactful than any other alternative over the short-to-medium term horizon.